)

Authors: Daniel Dominguez and Ross McGill

Welcome to the first in a series of articles designed to help financial firms in Argentina and Latin America understand some of the pit-falls and opportunities that result from trading in US securities or derivative financial products that reference US securities.

Financial firms in Argentina and Latin America face the same issues as those in any other country when it comes to compliance with US tax laws. The US is still, at least for the moment, the largest securities market in the world.

Many investors have US securities in their portfolio so it’s almost impossible for financial firms to avoid offering trading in US securities or derivative products that have underlying exposure to US securities such as CDVs, to their customers.

The difficulty for many financial firms is that they do not necessarily understand what they are getting into when they offer trading in US securities. Apart from the highs and lows and market fluctuations that drive much trading, investors who hold US securities long enough may also receive payments such as dividends or coupon payments on equities or bonds respectively.

When a US security (or derivative) is distributed, the payment often passes through a number of financial firms on its way from the original Issuer of the security to the ultimate beneficial owner. The US requires tax to be paid on such payments at a default tax rate of 30% unless the beneficial owner is entitled to a lower rate.

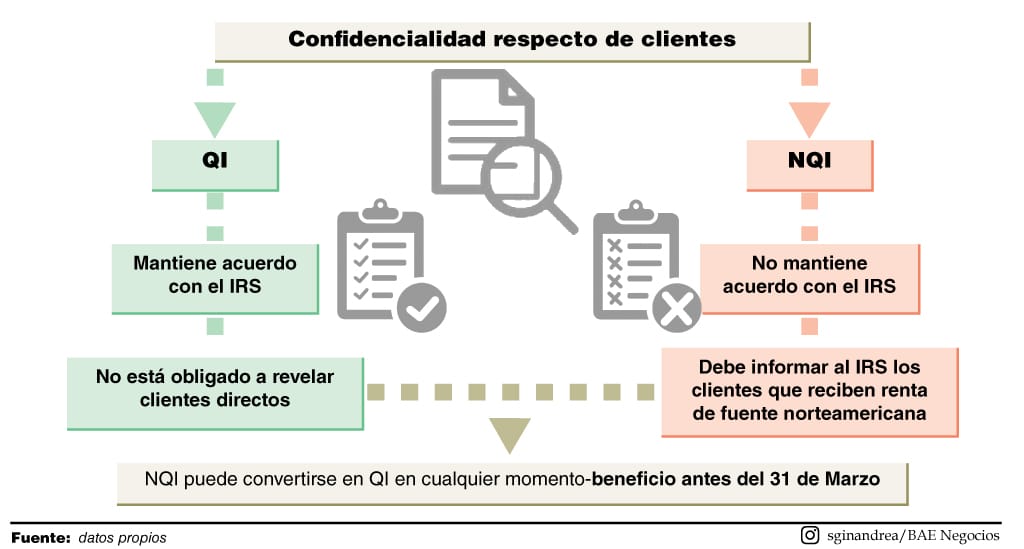

Even when there is no reduction from this rate, as is the case with Argentina because there is no double tax treaty between Argentina and the US, financial firms in the chain of payment must report the payments they make to each other to the IRS on Information Returns 1042-S each year and, in some cases, provide copies of those reports to their customers. The nature and number of these reports varies depending on the US classification of the financial institutions as either qualified intermediaries (QIs) or non qualified intermediaries (NQIs).

While the US QI program has been in effect since 2001, as far back as 2009, the US government publicly stated that it will treat any financial institution that is a non qualified intermediary as if it is facilitating tax evasion. The pre-requisite for any firm to be eligible for QI status is that its country’s Know Your Customer (KYC) rules must be approved by the IRS before any prospective QI can apply and sign a QI agreement. Now that Argentina’s KYC rules have been approved, the way is open for any financial firm that allows trading in US securities to become a QI.

But it doesn’t end there. Whether a firm is a QI or NQI, the very act of receiving US sourced payments on behalf of someone else, exposes that firm to several sets of regulatory rules in the US tax Code (called ‘Chapters’). The main ones are Chapters 1, 3, 4, 31 and 61 which all deal with the different ways that US securities (or derivative products that reference US securities) should be taxed and how the recipients of such income should be documented and/or reported.

As a result, there are some common problems that can occur perhaps because a financial institution has misunderstood the regulations, is not aware of the regulations or is deliberately trying to avoid them. In any of these cases, the US is not forgiving and a penalty from the IRS can substantially damage the reputation (and bottom line) of a financial institution. Here are just two issues.

Client confidentiality, data protection is a big issue for all financial institutions. But did you know that if you’re an NQI, you must report every single customer that receives US sourced income to the US government each year. That means that you must send to the US government your customer’s names, addresses, tax ID numbers and amounts of US sourced income they received during the previous year. The answer to avoid all that is to become a qualified intermediary. If you’re a QI, you have signed a contract with the IRS and, as long as you meet the obligations of that contract to document customers properly, withhold and deposit US tax in a timely way and report your payments annually to the IRS – you get some substantial benefits, not least of which are not being tarnished with the classification of NQI and you don’t have to disclose your direct customers to the US government. You can apply to be a QI at any time, although there is an additional operational benefit if you apply before March 31st. The biggest issue is that, while the application process is reasonably simple, the practical obligations of being a QI can be a bit daunting if you haven’t planned for them or you don’t have access to the tools you’ll need.

Avoid jail time. Under US tax regulations, every financial institution in the chain of payment must certify itself to the firm immediately above it in the chain, so that each firm knows how to treat its customer for US tax purposes. This is usually done with a US tax form called a W-8 (of which there are five types) and which are signed ‘under penalties of perjury’ by a person authorised to represent the firm. In other words, it’s a criminal offence to provide the wrong form or make false statements on these forms. However, Brokers are particularly vulnerable to making mistakes here because they will often take what is called ‘Title’ to the assets of their customers as part of their account opening and hold those securities in ‘street name’ (i.e. their name) at a financial institution above them in the payment chain. They believe, incorrectly, that, by taking title to the securities, they are also therefore the beneficial owner of the income derived from those securities. So, they use the US tax form W-8BEN-E to certify that they are the beneficial owner.

There is a simple test for those brokers to decide which US tax certification to make. If you receive a distribution (say a dividend), do you make a payment to any third party directly contingent on the receipt of that distribution? If the answer is yes, you’re not the beneficial owner for US tax purposes. In the case described, of course, the broker’s customer receives a payment to their account of that same distribution. In that case, while the broker may have title to the securities, from a US tax view, they are NOT the ultimate beneficial owner for tax purposes. The form W-8BEN-E was incorrect and the form W-8IMY indicating that the broker acted as an intermediary, was the correct form. This is a very serious matter because of that ‘penalty of perjury’ clause on the form. If its not corrected, the person who signed the form and the firm they represent are both at legal risk.

As an affiliate of the TConsult organisation, active in seventeen countries, we have access to a body of knowledge and practical experience that can help Argentine and Latin American financial institutions understand and comply with these complex regulations and avoid these types of potentially costly mistakes. If you’d like to know more, get in touch.